I never cared for Thomas Kinkade’s fantasy world of pink-lit stone cottages in dark woods, so, when I learned of his recent passing, I figured to keep my mouth shut on the “if you don’t have anything nice to say” principle. Interestingly, pretty much no one covering the story can resist mentioning – often in agreement – that many art critics did not care for his work. Why? That is, why bother beating on a guy’s life work only days after his death?

Kinkade’s cottages are hugely popular, so it is probably legit to call some of the criticism snarky elitism – populism is always controversial for the smaller cadres who feel personal investment in a medium. But the most interesting criticisms concern a topic of much relevance to us scholars of the 18th century: sentimentalism.

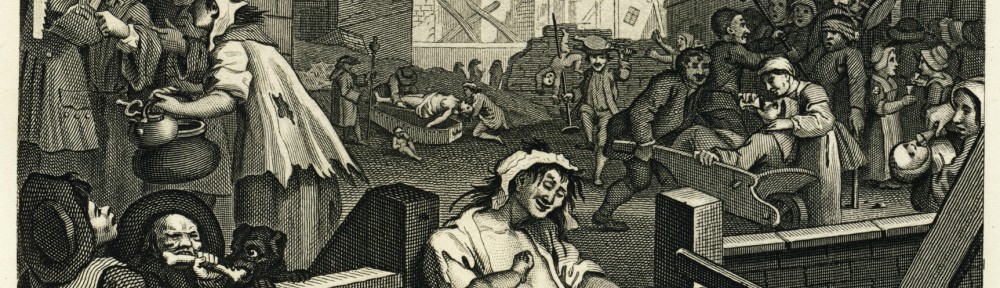

Sentimentalism, in this sense, is bad because is offers cheap emotion – or cheap grace, in Flannery O’Connor’s terms. It’s a kind of emotional – or, worse, spiritual – pornography. Kinkade’s world is such a pornographic world in which grace and transcendence are readily and immediately available at no cost (in fact, about $400 for a framed canvas).

But this isn’t primarily about Kinkade (though, for a thoughtful look at how some of his work is actually pretty good, see First Things web editor Joe Carter’s 2010 blog on the topic). This is about what to make of the sentimental. Gregory Wolfe, the always-thoughtful editor-in-chief of Image, nicely surveys the current state of thought on sentimentalism and offers his own insights in a 2002 blog on Kinkade. What most concerns Wolfe is that sentimentalism misrepresents reality. He quotes Kinkade saying he paints a world “without the Fall” and rightly objects that there is no such world. It’s one thing to paint a world before the Fall or even after Christ’s return and the inauguration of the new heaven and new Earth, but to remove the Fall from redemption history is to ignore sin and its attendant suffering and to obviate the need for Christ. Wolfe connects this neglect of sin with a desire to do away with ambiguity – for moral blacks and whites. Such absolutism eludes the need to show compassion, and to the extent that the message of Christ – found also throughout the prophets – is one of compassion, this absolutism, again, reveals that it has no use for Christ.

If this, then, is the bequest of our Enlightenment forbears, surely they were some kind of monsters! But, of course, it’s more complicated than that. There are clear problems with the doctrine of the innate goodness of humans, and it is monstrous to suggest that we can engineer ourselves into perfection, but the most interesting writers interested in sentimentalism were savvy enough to simultaneously critique it.

For example: Mackenzie’s Harley, the eponymous Man of Feeling, is surely a model of compassion and benevolence. But he is also so impractically ethereal that he dies of a broken heart despite his beloved returning his love. In the sentimental reconciliation between Matilda and Isabella in Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, the women’s immediate responsiveness to one another is frustrated by their own private competition for the love of Theodore.

Sterne, I think, is the most helpful and insightful on this score. In A Sentimental Journey, Yorick declares that “there is nothing unmixt in this world,” and means precisely that we humans cannot hope to attain to the emotional or spiritual purity promised by the thin and mawkish variants of sentimentalism. Sterne will not allow his reader to luxuriate in beneficent emotion precisely because he doesn’t believe we can ever be so purely beneficent – but that’s also what makes him so entertaining to read. He does not despair at our brokenness but laugh at it. And this is the power of Christ in Laurence Sterne: that, though sin has been defeated, we must never forget that we are among the Israelites or the Pharisees or the prostitutes, sinners, and tax collectors – but, by the grace of God, we can at least sometimes laugh at ourselves.

If this is enough to defend sentimentalism (to some extent), the obvious questions would be: For what? For Sterne, sensibility proves the existence of our souls. That’s something, at least. And for students of how imagination shapes culture, shouldn’t we be open to the possibility that our emotions, which must somehow be connected to our imaginations, reveal something to us about the world?

So, what do you think? Is this an adequate apologia for sentimentalism? Is there something worth retaining from this tradition, or are we too far gone down Kinkade’s forest path to recover?

The argument your present is the exact reason why I think Relief Journal is so needed. Presenting life as it really is, not sugar-coated or sinless, is part of our human experience and should be discussed, even though we are Christians. I resonate with O’Connor’s writings, the few that I have read. I found Kinkade somewhat old-fashioned because of the phrase he described himself as: painting a world without the Fall. There simply isn’t any justification that will convince me to overlook the pain and suffering in the world and laude a world like ours, but without that which makes us fallen. It feels like denial, and that’s not a sentiment I can get on board with.

It also feels as though Kinkade was trying something radically different from the sentimental writers. If he was writing about a world without the Fall, they were writing about characters so distraught by the sins and poor situations of others that they felt compelled to do something. That seems fundamentally different.

As for the path of sentimentalism, I can admire people that dream of better world to the extent that Kinkade, Mackenzie, and Walpole so far as they were gifted artists. I think there’s something to be said for studying their work and what they were trying to do. To the extent that sentimentalism requires some emotional response from the reader, it’s also admirable. But add me to the list of jaded, cynical Milleniums who can’t get behind something that’s so out of touch with my own experiences.

Kinkade’s work was never a favorite of mine, in part because I find it hard to believe that one person can truly understand and then portray to others what a world without the fall would truly like. To think that we could ever actually understand a world without a fall in such great depth, and would ever want to, might be somewhat ridiculous, though Kinkade may have had these same thoughts and ventured anyways. Kinkade’s work seemed to me less to express true life without a fall, and instead expressed life where for just a second everything seemed, though probably wasn’t, to be in place. It seemed more like the way one views life when they’re incredibly happy over good news, or relieved, and they start to filter anything potentially bad through a rose-colored lens, without letting any negativity in, even if for a moment. Kind of like a few seconds on Christmas Eve where everyone’s thankful and happy to be together, the food is good, the carols play in the background – but then someone says “So what do you think of Obama?” and debate ensues. (But maybe that’s just been my experience)

I too admire the sentamentalist’s work, I find their work knowledgable and helpful in that a critique of sentamentalist’s work gives insight onto what affects individuals in the society and classes of that time period. What we may feel sympathetic to or pity towards is bound to be somewhat different than those of Mackenzie’s time period.

Bkemps – I know those fleeting moments of joy you speak of, but I think they are wonderful precisely because of the suffering and pain we are normally aware of, because they are moments of the Kingdom breaking through and not “erasing” but redeeming pain. I like Sterne because he knows that the only legit sentimentalism must be realistic in this way.

I also was never a huge fan of Kinkade, although I grew up surrounded by him – my Grandma still LOVES him. Yet, I do think there is some value to art that represents what the world would be like without the Fall. C.S. Lewis writes of such a world as well. I think as Christians we often can get too bogged down with the brokeness that we can forget the original intention for humanity – one without sin. While this is not a place that I would advocate for spending extensive amounts of time, I think reminding ourselves that the current world was not the orignal plan can make the world that we do live in a bit easier to handle. We can more readily remember that the unfairness and brokeness of life was not what God intended. Without these kinds of remembers it can be easy to misplace the blame for our problems on God.

Aw nuts, I’ve always enjoyed receiving a greeting card sporting one of Kincade’s glowing, unrealistic cottages in the magic forest. The foot bridges across the pretty streams are especially nice. I guess i agree with the previous comment that it’s nice once in a while to let go of the swirl of death and destruction all around and within us and imagine what things woulda, coulda, shoulda been like, once upon a star. But this from a woman who still retains a childhood dream of being a mermaid, so I don’t know what such an opinion is worth.

How did you ever find this, Jean? It’s been a long while since I subjected my students to 18th century literature, but I would do a lot of things for an excuse to read Sterne.

I understand the interest in picturing a redeemed world, and I understand the pull of fantasy (I read lots of Lawhead and Tolkien as a child), but I guess I’m more Sternean (and Miltonic) in my own tastes. That is, I have always been suspicious of worlds of “pure fantasy,” and the more I think about it the more I think there’s something real at stake.

What I’d say now is that a world “without the Fall” would be a world other than God created, which is to suggest that He created an imperfect world or that what we want from this world is something other than what God offers us. I think something like Scorcese’s Bringing Out the Dead, Malick’s Tree of Life, or Robinson’s Gilead are much closer to a real Christian concept of beauty.

How did I find your blog? I recently put up a blog on WordPress and was looking for people I knew. I figured if you had a blog it would be good, and it is. If I ever figure out the tech side of WordPress my site might actually look nice one of these days.

In terms of your subject, I’d like to think there’s room for it all. I honestly never thought about Kincade’s art consciously as his attempting to portray a world without the Fall. I just got a nice feeling looking at the warm cozy houses. Pretty simple. I’d never classify his work as serious art, and I hope I’d never hang one of his paintings in my living room (wrong color scheme anyway) but an occasional nip doesn’t seem to harm.

I too have always been a bit “suspicious” of worlds of “pure fantasy,” which may sound like a contradiction after having said I don’t mind Kincade’s paintings in small doses. As wild as my imagination was as a child, and as addicted to the Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella stories as I was, I still generally preferred literature and movies that portray things more like life really is. I lived in Europe too long for the hyper-realism of their films and general world view not to affect me. The Tolkien books plumb wore me out as a middle school kid, trying to keep track of make-believe worlds and people. The “real world” taxes my soul quite enough.

In any case, your post was excellent and definite food for thought, Brad. I’ll have to check out those movies.

On the other hand, a movie like The Truman Show is completely implausible, yet it teaches something a purely real-life film couldn’t, by exaggerating the absence of reality.